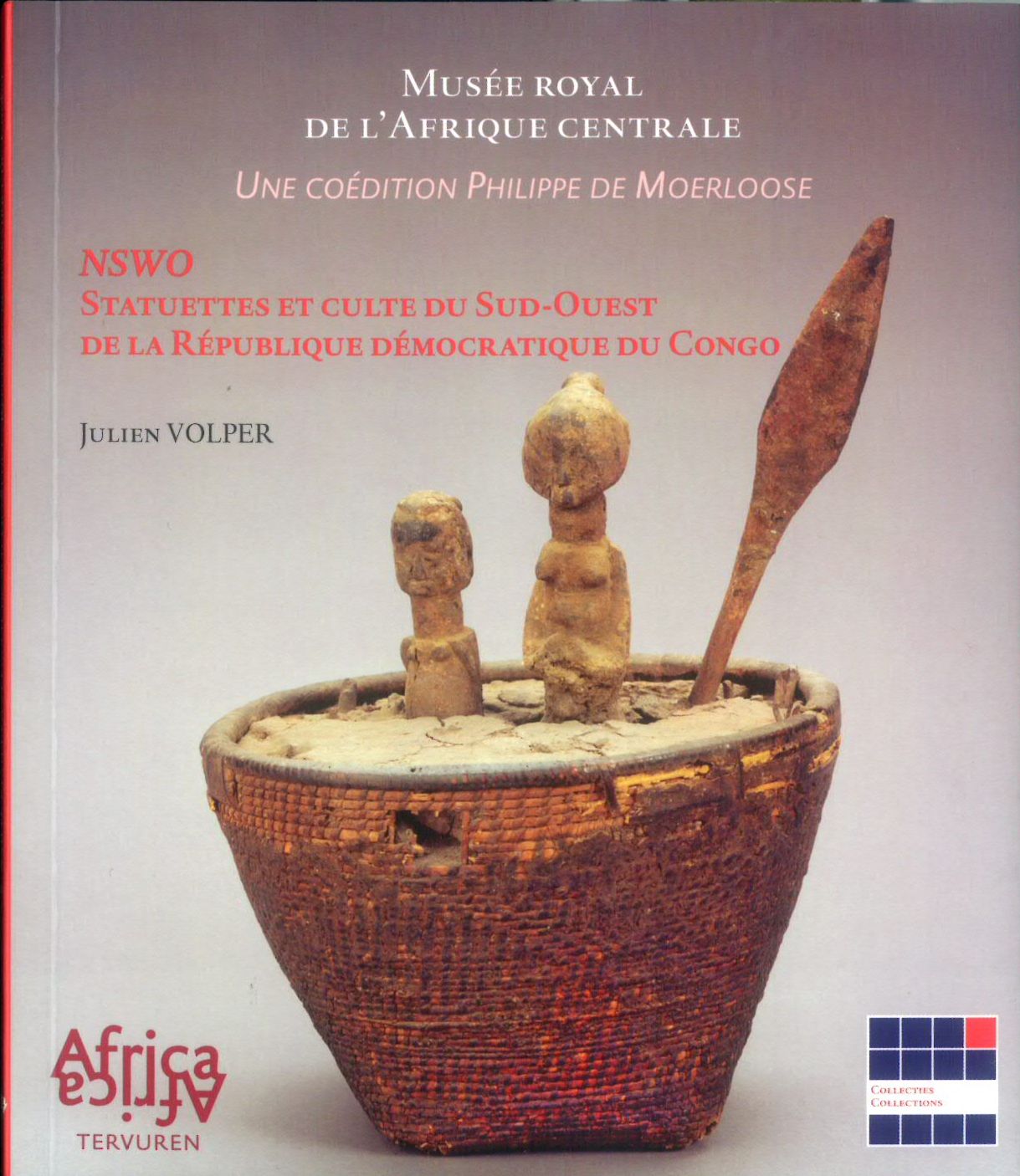

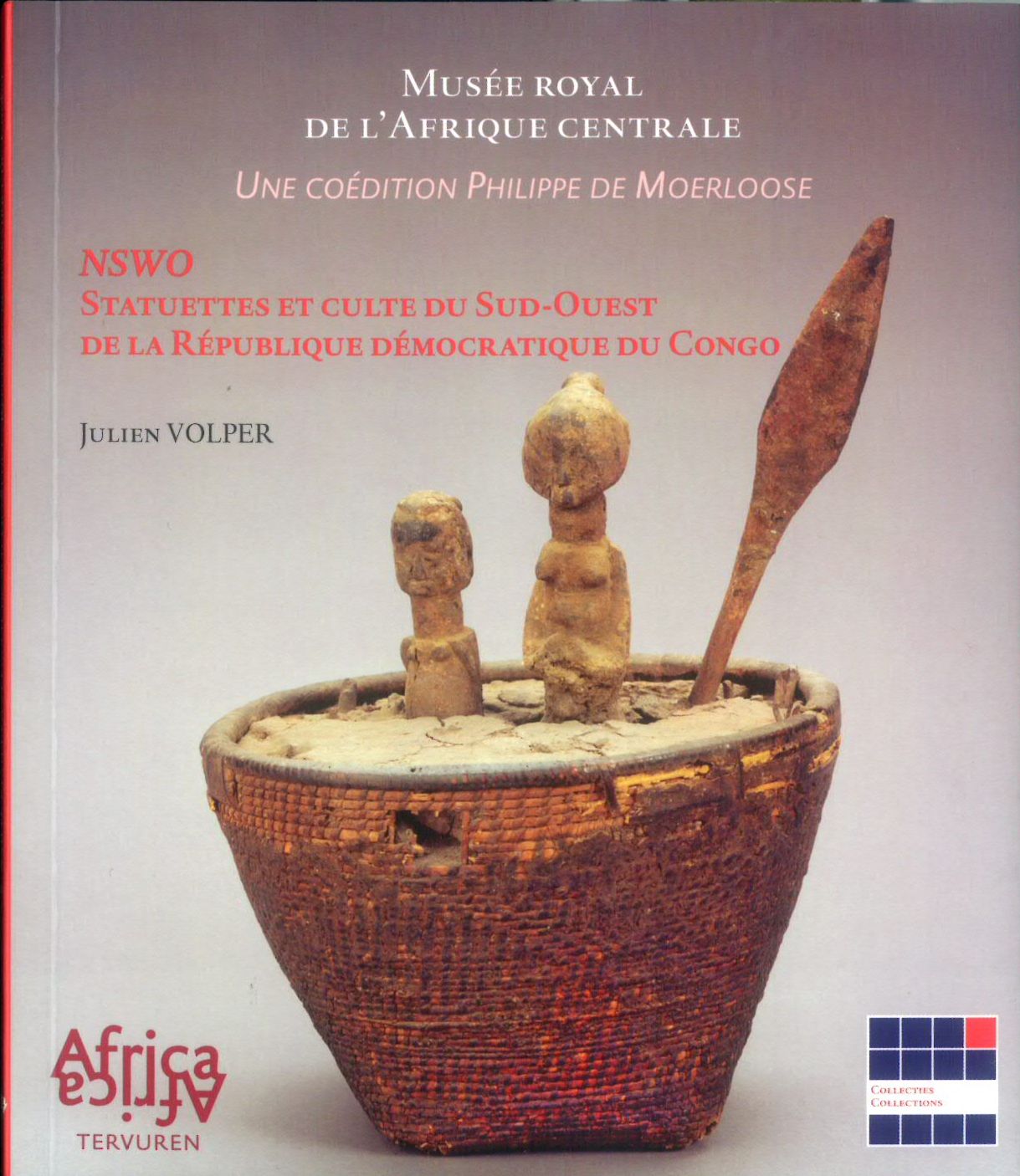

Royal Museum for Central Africa researcher Julien Volper is a very active writer on Congolese art (just search for his name on this website !).

His forte is clearly to get every bit of overlooked information from archives, old photographs and objects in order to build an overall view on a specific

art form. This way of working can lead to a flood of sometimes contradictory information, which may leave the reader a bit confused.

That’s not the case with his latest work, which acquaints the reader with an art form and a cult he has probably never heard of.

The nswo is a religious tradition of a number of ethnic groups in the Bandundu province of DRC, including the Yansi, Sakata, Hungana, Buma,

Mfunuka, Tsong, Mbala, Teke, Dikidiki, and Yaka. This spirit is embodied in small, rather simple, figures, a sizeable number of which are

in the collections of the Tervuren Museum and are illustrated in this booklet.

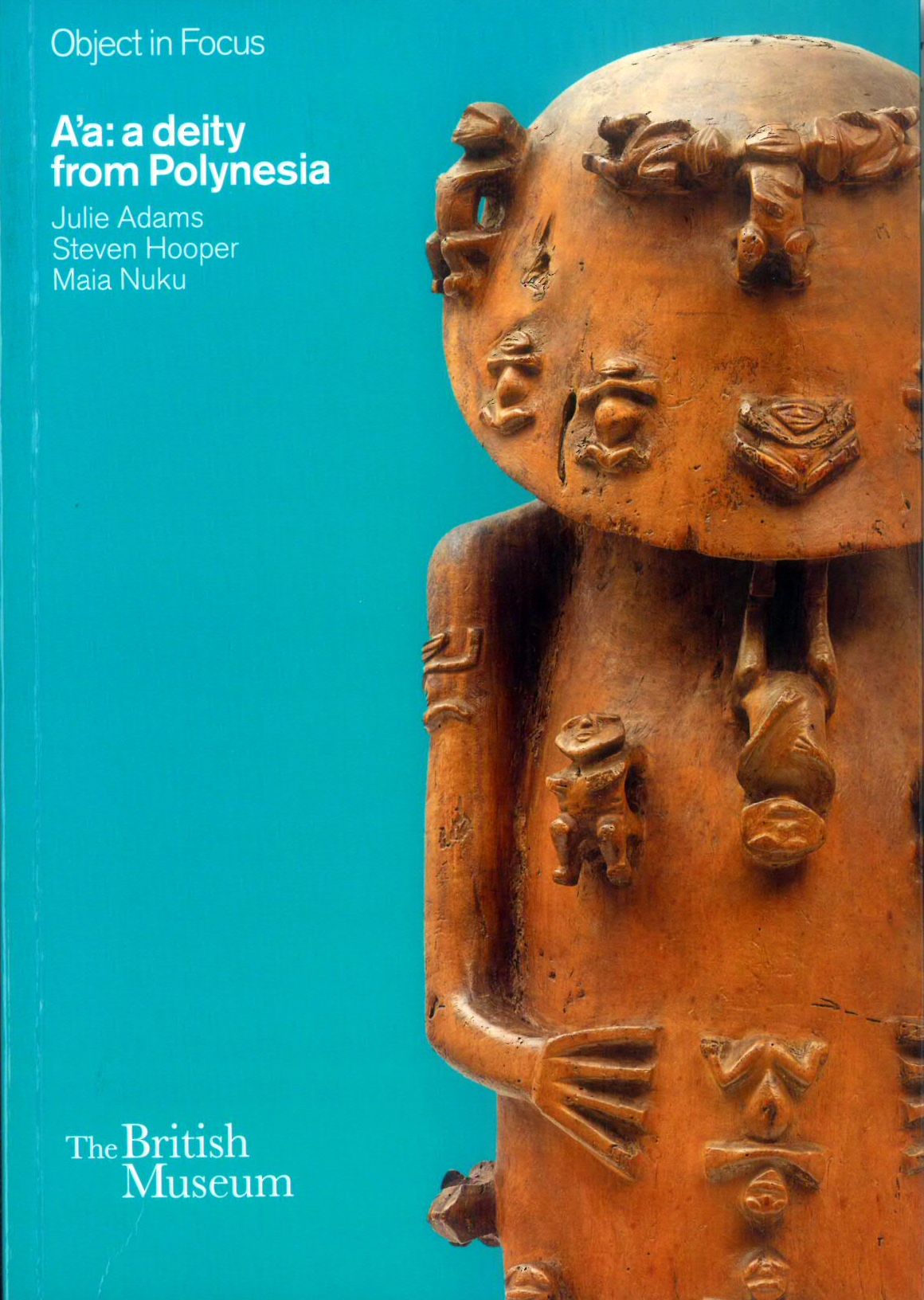

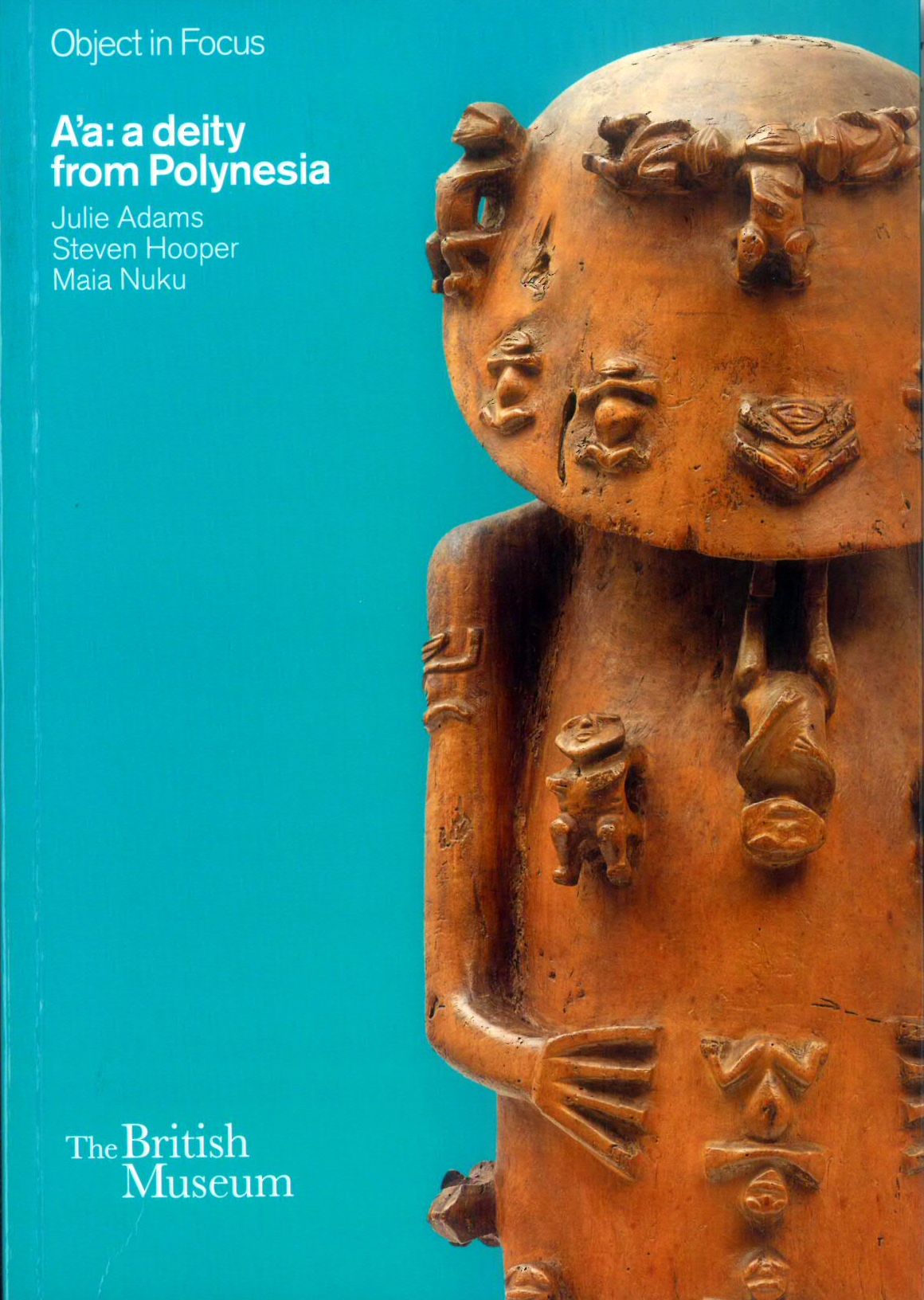

A’a: a deity from Polynesia, by Julie Adams, Steven Hooper and Maia Nuku. Published by the British Museum, 2016

This small booklet, like the one on the Ife head, is part of a collection devoted to single masterworks in the collection of the British Museum.

This one on the most famous Polynesian figure is based on the one hand on new scientific tests of the figure and, on the other hand, on a 2007

article by James Hooper on the same topic. It demonstrates quite conclusively that this large figure from the little know island of Rurutu

(Austral Islands) was actually a reliquary for the skull and long bones of a very important ancestor, packed in tapa and red feathers and

removed before handing the figure to the London Missionary Society in 1821.

This interpretation seems however contradictory with a very speculative one exposed by Julie Adams, which would link it to Christian ideas that

would have been supposedly brought from England by prince Omai of Tahiti.

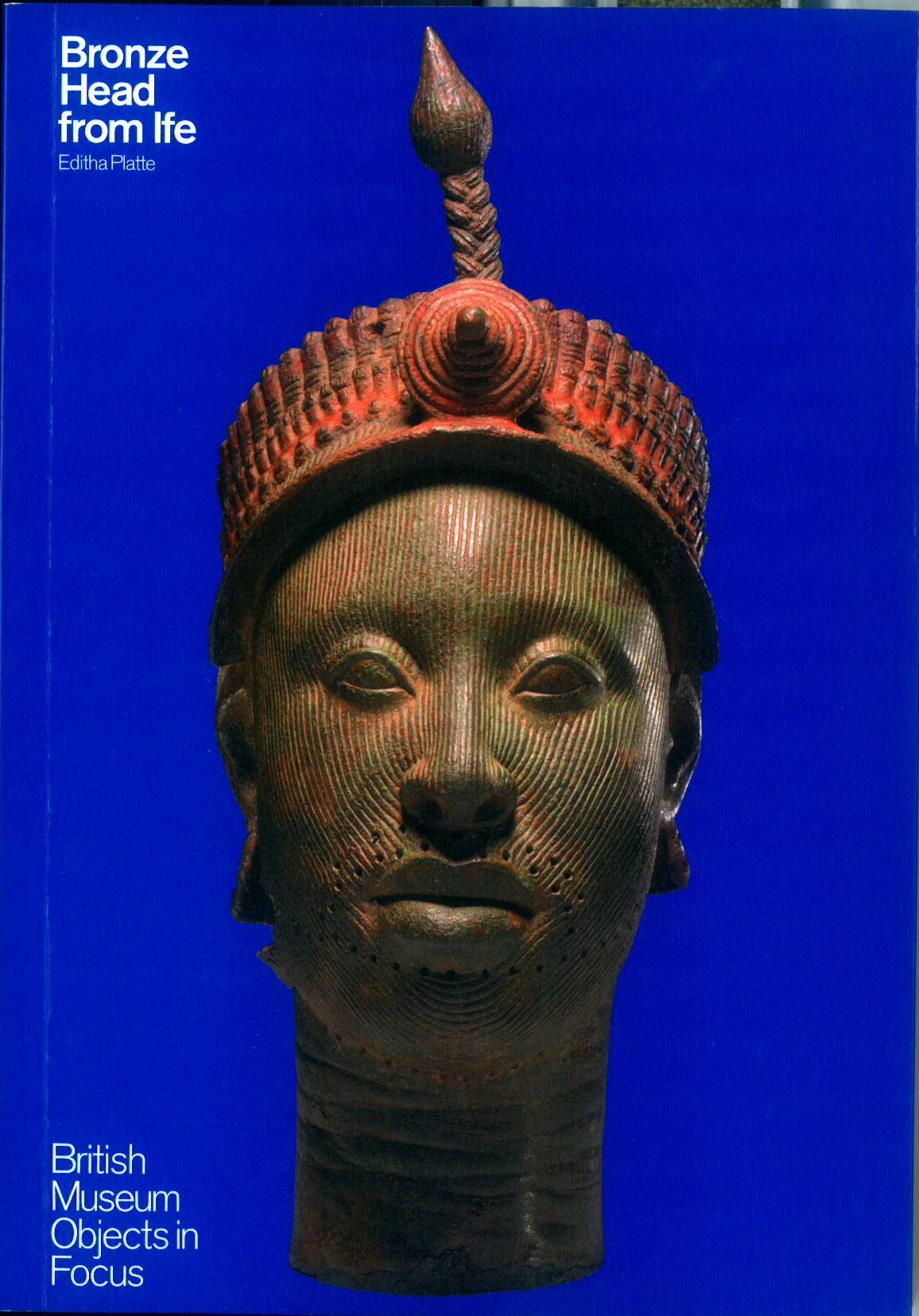

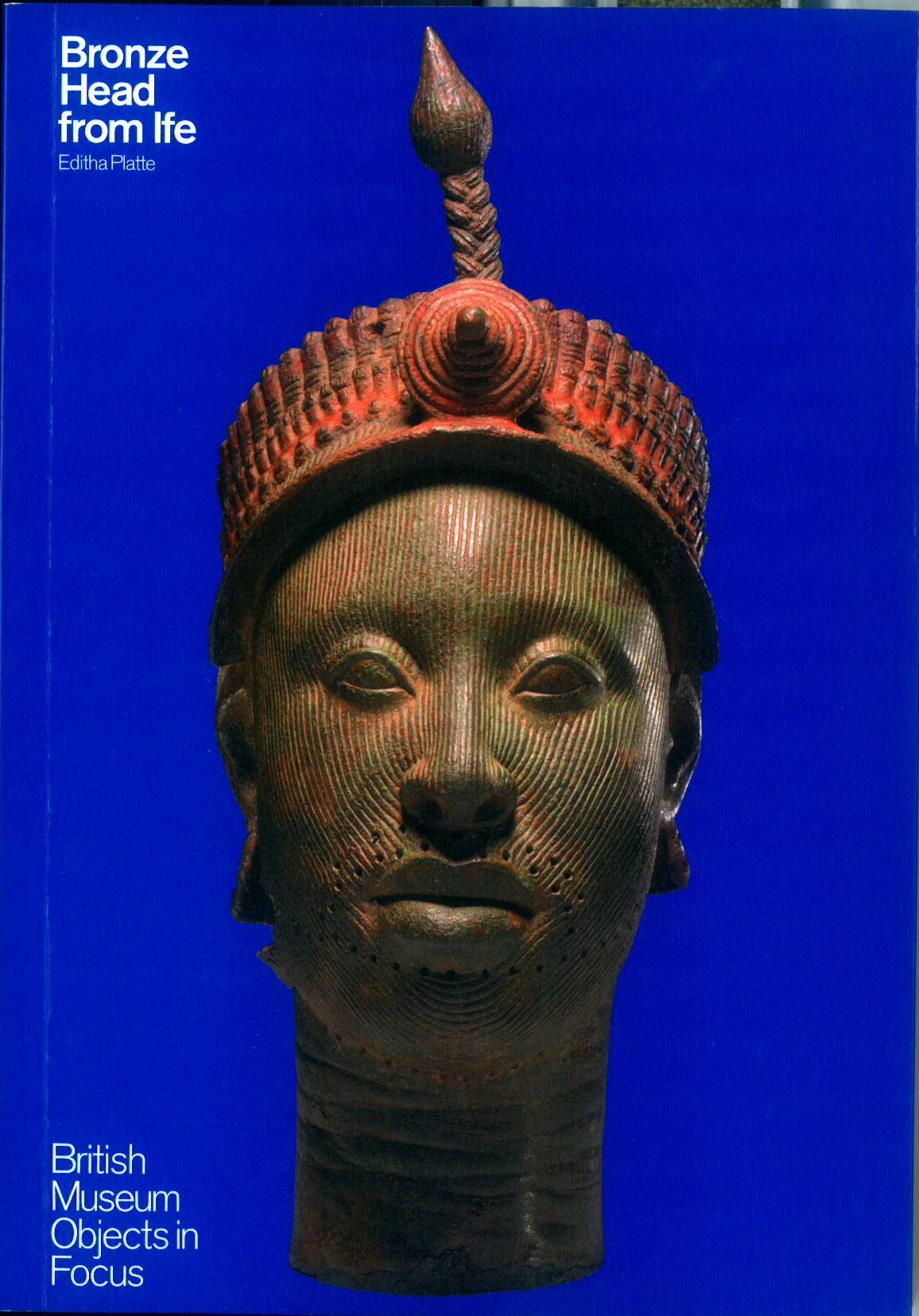

Bronze Head from Ife, by Editha Platte. Published by the British Museum, 2010

This booklet is part of a collection entitled “British Museum Objects in Focus”, in casu the famous brass head excavated in Ife in 1938 by Bernard

Fagg.

The book deals mainly with the “social life” of this sculpture, i.e. how it was received at the time and nowadays both by the Western public

and by Nigerians themselves, including its use as a branding logo. So, most of the pages are devoted to how the head changed the Western views of

African art, how it influenced British artists and how it is heralded as a symbol of Nigerian culture and history.

As Mrs. Platte is a field worker, it is therefore surprising that there isn’t more on the Ife culture and history and how the head would fit

in. As she is also a specialist of gender studies, it is even more surprising that there is no discussion of the intriguing view of the present-

day Oni that the head doesn’t represent a king but a queen.

Baule monkeys, by Bruno Claessens and Jean-Louis Danis. Published by Mercatorfonds, Brussels, and Africarium, 2016

Collector Jean-Louis Danis buys an unfinished Baule monkey figure in a New-York flea market. Years later, he hires future Christie’s expert

Bruno Claessens to document his collection. And in the end, we all get the pleasure of this new richly illustrated monograph on Baule monkeys !

This is probably one of the more thorough analysis of one of poorly documented art forms in Africa. Without any local knowledge or travel in the field,

Bruno Claessens has drawn on every possible line of enquiry available in Europe and the US. He has found early 20th century photographs buried in archives,

uncovered errors in the common descriptions, used the Yale Van Rijn Archive of African Art but, mostly, he has dug information from the published and unpublished

research of Suzanne Vogel and Alain-Michel Boyer.

We learn that these very characteristic figures are made in great secret to become the abode of dangerous bush spirits, the amuin.

They are made to look fearsome and ugly, representing baboons or chimpanzees, aggressive animals from the uncivilized bush, yet disturbingly close to

humans. They then need to receive regular offerings of blood and eggs (their greediness symbolised by their begging bowl) in order to protect the

supplicant and his community. Unless they are fed sufficiently, they could turn against their keeper, which is probably why younger generations

preferred them shipped away to the white people rather than standing unsatisfied in their neighbourhood !

Overall, a highly informative and comprehensive work, well structured and properly edited with numerous, often full page, photographs.

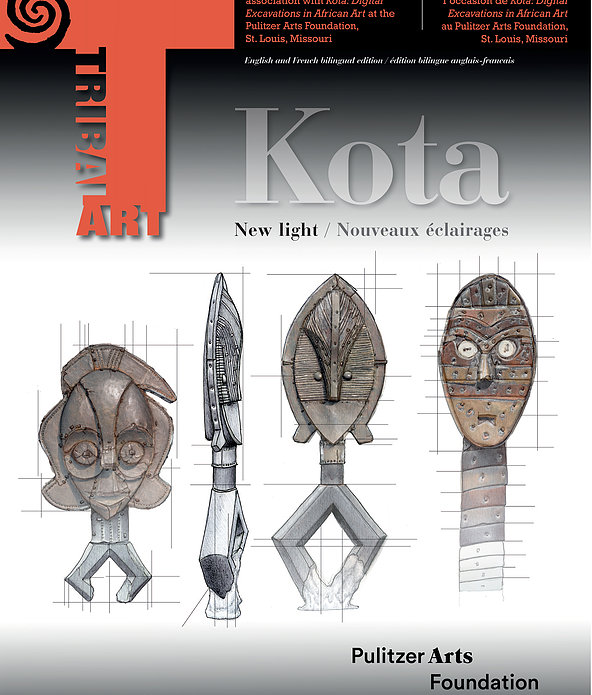

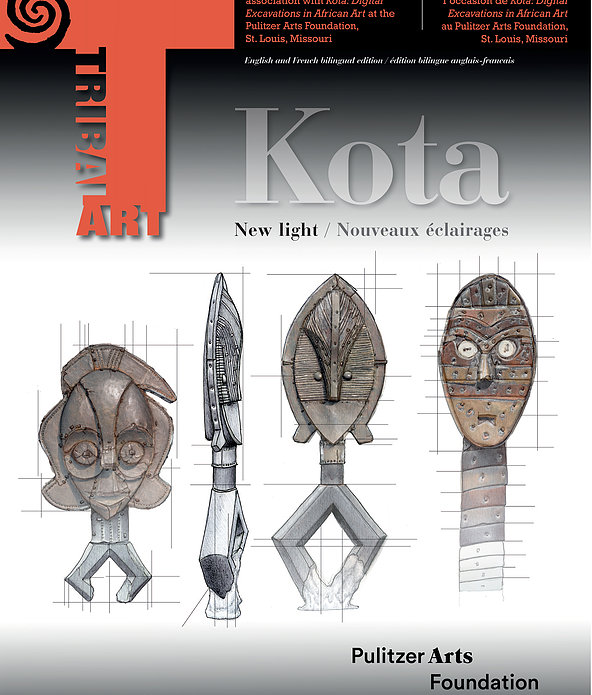

Kota. Digital Excavations in African Art, by Frédéric Cloth and Kristina Van Dyke. Published by the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St. Louis MO, 2015

Kota, New Light. Special Issue #5 of Tribal Art Magazine, Arquennes, 2015

Most readers of this website know first hand that African art can be an overwhelming passion. However, none of them pushes it as diligently

and as intelligently as Frédéric Cloth. For years, Frédéric has assembled documentation on about 2000 so-called Kota reliquary figures, drew

hundreds of them on a scroll (a work of art in itself !) and input in a database tens of factual descriptors for each of them.

Contrarily to what might be expected, close to nothing is known about these reliquary figures (which, by the way, were not made by the Kota

but by various people more to the East of Gabon !). So taking advantage of the large size of the corpus and of the its great consistency,

Frédéric Cloth, who is a computer engineer, decided to apply the law of statistics to make “digital excavations” in that corpus. With astonishing

results! The most provocative of which being that these figures originally came as triads of one convex face, supposedly male, and two concave

ones, supposedly female, one being more decorated than the other.

This huge and very innovative work is poorly served by the two publications that go with an exhibition at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation to

explain it and demonstrate the results with a selection of figures: a beautiful cardboard leaflet published by the Foundation and illustrated

with Frédéric Cloth’s own drawings (including a tentative time-line of the production of those reliquaries) and a supplement of Tribal Art

Magazine which includes articles by other authors as well. Even combining the two publications, we are left with more questions than answers

and the frustration of having access only to a small part of the experience.

Frédéric, what about putting your database and your visualisation interface online ?

This is the “catalogue” of the maiden exhibition by the new MEG in Geneva Moche Kings. Divinity and Power in Ancient Peru.

The exhibition itself is an impressive ensemble not only of ceramics and jewellery but also of mural friezes either original in clay and organic pigments

(from the 6th century AD !) or in real size HD photographs. The centre and main attraction however is the world-premiere show of the extravagant

content of a newly discovered tomb: that of the so-called Lord of Ucupe, excavated by the author Steve Bourget.

The companion book to the exhibition is not really a catalogue : many of the 300 pieces loaned by European (mostly Berlin and Stuttgart) and

Peruvian museums are not even mentioned, let alone reproduced. It is a cross-over between an excavation report of the Lord of Ucupe tomb and an

essay on the nature of political power in the Moche culture.

Steve Bourget, who had recently curated an exhibition at the Musée du Quai Branly on another aspect of Moche culture,

the link between sex, death and human sacrifice, leads the reader from these newly discovered regalia, to the analysis of their iconography to conclusions on the nature

of the Moche political power. This is a fascinating detective work of comparison and deduction, even if I felt at some times that the conclusions overreached

the material evidence. And the recently restored objects (with financing from the MEG, hence the priority they got in showing them) are sumptuous.

In retrospect, however I would have skipped the reading of the central part on the description of the excavation, layer per layer (20 of them !)

Most of the readers of this website probably know about Michael Rockefeller, son of one the richest and most powerful man in America: Nelson Rockefeller,

governor of New York, vice-president of the United States and, most importantly to us, founder of The Museum of Primitive Art. Michael himself

was a trustee of the Museum and, after his studies at Harvard, left for Dutch New Guinea, joining a Harvard expedition to the Dani in the Highlands

and then visiting the Asmat on his own, i.a. to collect works of art.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the wing for the collections of Pacific and African art, successor to the Museum of Primitive Art, bears his

name and houses his impressive collection of Asmat art.

The

journal of his trips, together with 600 photographs, was published in 1967 by The Museum of Primitive Art.

On November 17th 1961, the dug-out catamaran on which he was with Dutch anthropologist René Wassing and two Asmat teenagers overturned off the

Asmat mangroves and began to drift to the open sea. Michael Rockefeller, aged 23, decided to try to swim to the coast, estimated to be 12 miles

away and home to sharks and saltwater crocodiles. He disappeared and, despite a huge rescue operation, no trace of him was ever found. He was

declared legally dead by drowning.

Despite that official position, inevitably doubts and rumours have lingered on.

Now, more than 50 years on, journalist and adventurer Carl Hoffman, author of books like The Lunatic Express:

Discovering the World . . . via Its Most Dangerous Buses, Boats, Trains, and Planes, has gone to the Asmat villages and to Dutch small towns,

meeting Asmat elders, retired Dutch missionaries and officials, willing to speak. He has written a kind of real-life detective story and uncovered

the truth.

Not only has he found all the precise details of Michael Rockefeller’s disappearance and death but he also has the explanation why this has

remained a mystery for so long.

Gripping and deeply disturbing. You will never look at a bis pole the same way.

Finally we hear something else from Sierra Leone and Liberia than Ebola !

This book is part exhibition catalogue and part collection of essays. The Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA), alongside several other US

museums, had received an important gift of works from those countries by the late William Siegmann. He was last curator of African and Oceanic

art at the Brooklyn Museum but, before that, he had been for many years director of the Africana Museum at Cuttington University (Liberia) and

of the National Museum of Liberia.

Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers, curator at the MIA, has now put up an exhibition around the Siegmann collection, that gives an extensive view of the

art of nearly all the ethnic groups in the region from the Bullom to the North to the Kru to the South, the Bassa on the coast to the Loma in the

highlands.

Even more interesting than the fully illustrated catalogue for those of us who can’t make it to Minneapolis is the first part with articles on

the identification of Sande masks carvers by Frederick John Lamp, Dan masquerades by Daniel B. Reed, brass casting by Barbara C. Johnson and the

ancient stone sculptures by Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers himself. It makes the book a reference on the region.

That African masks are not made to stand statically in a museum case is an obvious point, that has been made clear in several books and articles

most notably in Robert Farris Thompson’s African Art in Motion back in 1974.

The additional point made in this collection of essays by Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, curator at the Africa Museum in Tervuren, is that

many of those masquerading traditions are still alive and well.

Each article (some of them are in English, some in French) deals with a specific ethnic group and masking tradition. Those who know her won’t

be surprised that Anne-Marie Bouttiaux herself deals with the Guro. Other topics are komo masks with the

Minyanka (Philippe Jespers), the pretty unknown (by collectors) Bedik masks in Senegal (Marie-Paule Ferry), various traditions in Guinea (Fredrick

John Lamp), koui masks of the We (Bony Guiblehon), bedu masks of the

Nafana, Kulango and their neighbours (Karel Arnaut), Bobo masks (Guy Le Moal), sigma masks of the Gur-Grushi

peoples in northern Ghana (Cesar Poppy) and egun masks from the Yoruba established in Ouidah (Joël Noret).

Being the proud owner of bedu masks, I started with Karel Arnaut’s essay and I found out that these

anthropological articles are sometimes a though read for lay collectors !